One of my PhD research aims, as well as a crucial aspect of the study of Nubian goldsmithing, is to outline the possible goldsmith techniques involved in Nubian jewellery making, especially during the Kerma times.

Identity and technical skills of local craftsmen seem already attested by the Early Kerma jewels (c. 2500-2050 BCE). Among them, interesting cowrie shell reproductions made in precious metals and stone, gold and calcite, were found (Markowitz, Doxey, 2014). Ten base gold cowries were confirmed by Reisner at Kerma (K 5611) among the beads attached to the typical Nubian leather skirts (Reisner, 1923). Cowries are present also in Kerma assemblages recently investigated in the 4th Cataract. Moreover, these shells fixed on leather bands and used as personal body adornments were found in Gash Group tombs (early 2nd millennium BCE) (Manzo, 2012). This practice is still attested in Aksum and Adwa areas, Tigray, Ethiopia, decorating mahasal, gorfa – maternitytools – and necklaces for children and women (Silverman, 1999). European traveller accounts suggest particular customs of Sennar women such as the wearing leather skirt with cowrie belt sewed, to protect fertility and sexuality (Cailliaud, 1826; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fC9O_Wc50wo).

An exquisite example of cowrie necklace in gold, imported from Egypt or made locally, comes from the grave 3, at Uronarti (Fig. 1). This site is one of the Middle Kingdom Egypt strategic forts, such as Askut, Buhen, Mirgissa, Semna and Kumma, linked to trade and gold mining operations (Lacovara, Markowitz, 2019; Markowitz, Doxey, 2014). In comparison with the Middle Kingdom cowrie jewellery, the gold cowries of the Uronarti necklace seem to be quite different from each other. They have irregular shapes and notches, probably not made through the use of a mould like those Egyptian but worked individually with chisels and burins. The central pendant seems differently manufactured, extremely precise, probably made with the lost wax technique. Gold cowrie reproductions appear again in Meroitic goldsmithing. For example, the beautiful cowrie jewels of the Queen Amanishakheto (Fig. 2), display female and warrior symbolism (Aldred, 1978; Lacovara, Markowitz, 2019; Manzo, 2011; Markowitz, Doxey, 2014; Wilkinson, 1971). The technique used in the cowrie reproductions seems to be the same process that was used in Egypt and attested by the cowrie-shell girdles found in the tombs of the 12th Dynasty royal ladies, at Lahun and Dashur: the welding of two halves (Fig. 3).

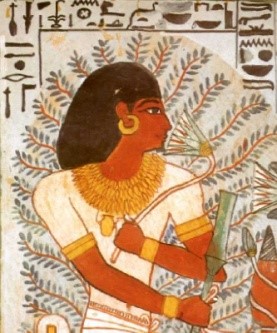

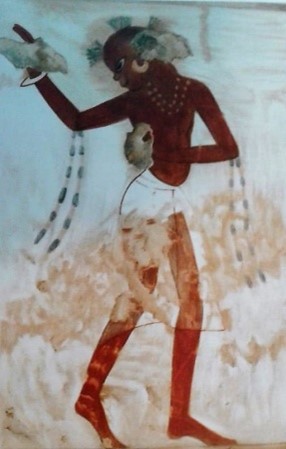

A particular typology of ornaments that could attest to the influence of the Nubian style on Egyptian goldsmithing are the penannular earrings (Fig. 4). Already found among the Early Kerma ornaments, they appear as a typology in Egypt only during the New Kingdom. In the shape of a small ring with an opening in the circumference, the hoop earrings are an interesting Nubian identity marker and at the same time a Nubian ethnic topos, recovered from Kerma burials at Tombos (Smith, 2003). During the New Kingdom traditional Nubian styles and jewellery were introduced to Egypt and adopted by Egyptians (see Lacovara, Markowitz, 2019).

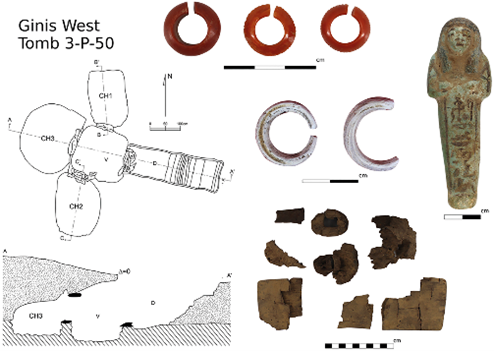

The penannular earrings appear in Egyptian jewellery made of gold, probably created with the common technique of two halves welding (e.g. Sennefer tomb, TT 96) (Fig. 5). An example comes from the tomb of Horemheb (TT 78) dated to the reign of Thutmose IV (c. 1400-1390 BCE). A dancer is depicted with a haircut typical of those worn in Sudan even today, an ivory bracelet, a necklace with gold beads, armlets with attached beaded streamers and a penannular earring, probably in gold (Lacovara, Markowitz, 2019) (Fig. 6). A late Ramesside example of penannular earrings, in carnelian, jasper and shell/ivory/bone, comes from one of the most remarkable tombs in the MUAFS concession, 3-P-50, at Ginis West (Lemos, 2022) (Fig. 7).

From a technological and typological point of view, these jewels help us to outline a native Nubian style that influenced and built Nile Valley goldsmithing with specific identities. Nubian technology shows a deep knowledge of the goldsmithing process, from the finding of the raw material (mining, wadi-working, panning), its transformation (smelting, casting) and working (hammering, welding, polishing), until the final result: the jewel, a story waiting only to be read and told.

We are only at the beginning of our journey into the ancient Nubian goldworking and goldsmithing, and we eagerly await the opportunity to get back on the field… stay tuned!

References

Aldred C., 1978, Jewels of the Pharaohs. Egyptian jewellery of the Dynastic Period, London.

Cailliaud F., 1826, Voyage a Mèroè, au Fleuve Blanc, au Dela de Fazoql, Paris.

Lacovara P., Markowitz Y.J., 2019, Nubian Gold. Ancient jewellery from Sudan and Egypt, Cairo, New York.

Lemos, R, 2022, Can We Decolonize the Ancient Past? Bridging Postcolonial and Decolonial Theory in Sudanese and Nubian Archaeology, Cambridge Archaeological Journal: 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774322000178

Manzo A., 2011, Punt in Egypt and beyond, Egypt and the Levant 21: 71-85.

Manzo A., 2012, From the sea to the deserts and back: New research in Eastern Sudan, British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan 18: 75-106.

Markowitz Y., Doxey D. M., 2014, Jewels of Ancient Nubia, MFA Publications, Boston.

Reisner G. A., 1923, Excavations at Kerma. Parts IV-V, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., U.S.A.

Silverman R., 1999, Ethiopia. Traditions of Creativity, University of Washington.

Smith S. T., 2003, Wretched Kush. Ethic identities and boundaries in Egypt’s Nubian Empire, London.

Wilkinson A., 1971, Ancient Egyptian Jewellery, London.