I recently passed my PhD viva at Cambridge and thought it would be nice to provide an overview of the work I’ve been carrying out in the past 4 years, which informs a lot about my research for DiverseNile. Firstly, there are many people to whom I’d like to say thank you—they’re all named in my thesis—but here I will just mention a few key individuals in my journey from Cambridge to Munich: Kate Spence, Stuart Tyson Smith, Paul Lane and our PI Julia Budka.

My thesis is entitled ‘Foreign Objects in Local Contexts: Mortuary Objectscapes in Late Colonial Nubia (16th-11th Century BC)’. From the title, you might be asking what do I mean by ‘Late Colonial Nubia’? It’s not my intention to discuss this here, but in my thesis I argue that we should rethink the terminology we use to describe Nubia’s history from a bottom-up perspective. At this point in my discussion, ‘Late Colonial’ means ‘New Kingdom’ Nubia, although after discussing this with Stuart Smith I realized that there’s more nuance to add to my bottom-up discussion of chronology. I hope to be able to talk about this in more detail soon.

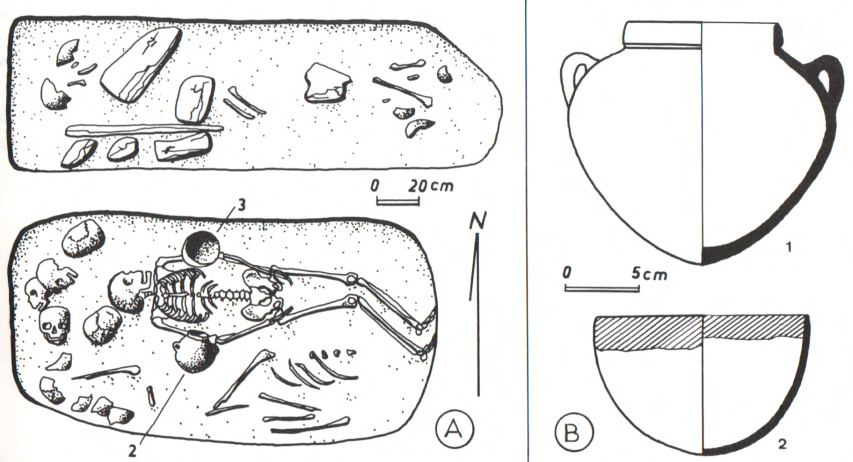

In the Late Colonial Period (or New Kingdom), a huge set of Egyptian-style objects flooded Nubia. This global objectscape appears at various sites from the 1st to the 4th cataract. In my thesis, I explore how colonization materialized differently across Nubia through the reception, adoption and transformation of Egyptian-style objects in local contexts. By examining the social role performed by foreign objects in local contexts in Nubia, my thesis firstly unveils the existence of various burials communities which adopted and combined foreign objects in different ways to fit social spaces’ rules and styles. This is given in the different distributions and combinations of the same types of standardising objects at various sites and social spheres, similarly to the way people around the globe later consumed industrialised tea sets, revealing alternative social structures either potentializing or limiting cultural practices created by the same global objectscape (e.g., cup + saucer versus beaker + saucer).

But what kind of social contexts did the same objectscape create in various local contexts? For example, at the same time foreign heart scarabs materialised colonisation, they could also create alternative social contexts within Nubia. Heart scarabs allowed individuals buried at elite sites, e.g. Aniba, Sai or Soleb, to display cultural affinities with Egypt and their power to consume restricted foreign objects, but at the non-elite cemetery of Fadrus, where a single heart scarab was found amongst c. 700 burials, these objects seem to have perform a different role reinforcing community and solidarity. In between extreme alternative social realities (elite versus non-elite), foreign objects were received and adopted in various ways, but also materially transformed or “copied” following local expectations and demands. In my thesis, I discuss more closely the roles performed by standardising scarabs/seals, jewellery, shabtis and heart scarabs in the shaping of alternative social realities within Nubia. This resulted in social complexity and cultural diversity in a context of colonial domination and attempted cultural homogenisation through objects.

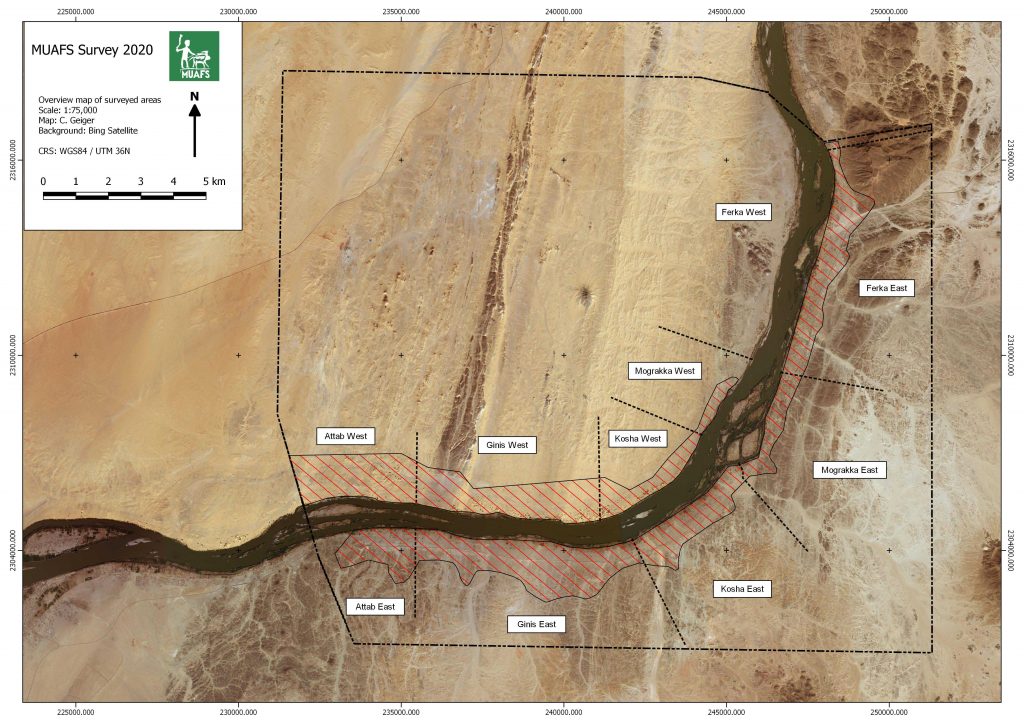

In other words, my thesis investigates how the same types of objects ended up shaping complexity and diversity in Late Colonial/New Kingdom Nubia, despite ancient colonisation and modern homogenising, colonial perspectives to the archaeology of Nubia. My PhD approach informs a great deal about my current research for DiverseNile, which focuses on the variability of mortuary sites and material culture within Nubia, where I have the opportunity to explore in detail a ‘peripheral’ context which becomes the ‘centre’ of alternative experiences of colonisation.

Further reading

Lemos, R. 2020. Material Culture and Colonization in Ancient Nubia: Evidence from the New Kingdom Cemeteries. Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology, ed. C. Smith. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51726-1.

Pitts, M. 2019. The Roman Object Revolution. Objectscapes and Intra-Cultural Connectivity in Northwest Europe. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Versluys, M.J. (2017). Object-scapes. Towards a Material Constitution of Romaness?. In Materialising Roman Histories, ed. A. van Oyen and M. Pitts. Oxford: Oxbow. 191-199.

Smith, S.T. 2021. The Nubian Experience of Egyptian Domination During the New Kingdom. In The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia, ed. G. Emberling and B.B. Williams. Oxford Handbooks Online https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190496272.013.20.