The most significant category of material culture utilised by the DiverseNile project in order to reconstruct contact space biographies (see Budka et al. 2025) in the Attab to Ferka region is pottery. It is therefore with great pleasure that I can announce the recent publication of several articles on pottery and the varied perspectives on its analysis.

As previously stated on this blog, an article was published that examined the significance of Nubian pottery in the context of Sai city, thus in an urban environment in Upper Nubia during the 18th Dynasty (Budka 2025a).

A recent update was presented together with Giulia D’Ercole and Elena Garcea, addressing the subject of archaeometric analyses of Sudanese ceramic assemblages from all archaeological periods, spanning from the ninth millennium BCE to the first millennium BCE. The present article (D’Ercole et al. 2025) discusses some of the findings of my ERC-funded projects, AcrossBorders and DiverseNile.

It is with great satisfaction that I can report on the successful inclusion of novel research findings from the field in Sudan, with fresh samples, in this publication. This achievement is to be attributed to the invaluable support of our esteemed colleagues at NCAM, and in particular, our inspector during the 2025 season, Mohamed Eltoum.

In view of the ongoing war in Sudan, it is imperative to continue our collaborative analysis of material using state-of-the-art methods. This will enable Sudanese archaeology to make progress despite the current difficulties and major concerns, apart from the humanitarian catastrophe, such as the destruction of museums, universities and offices.

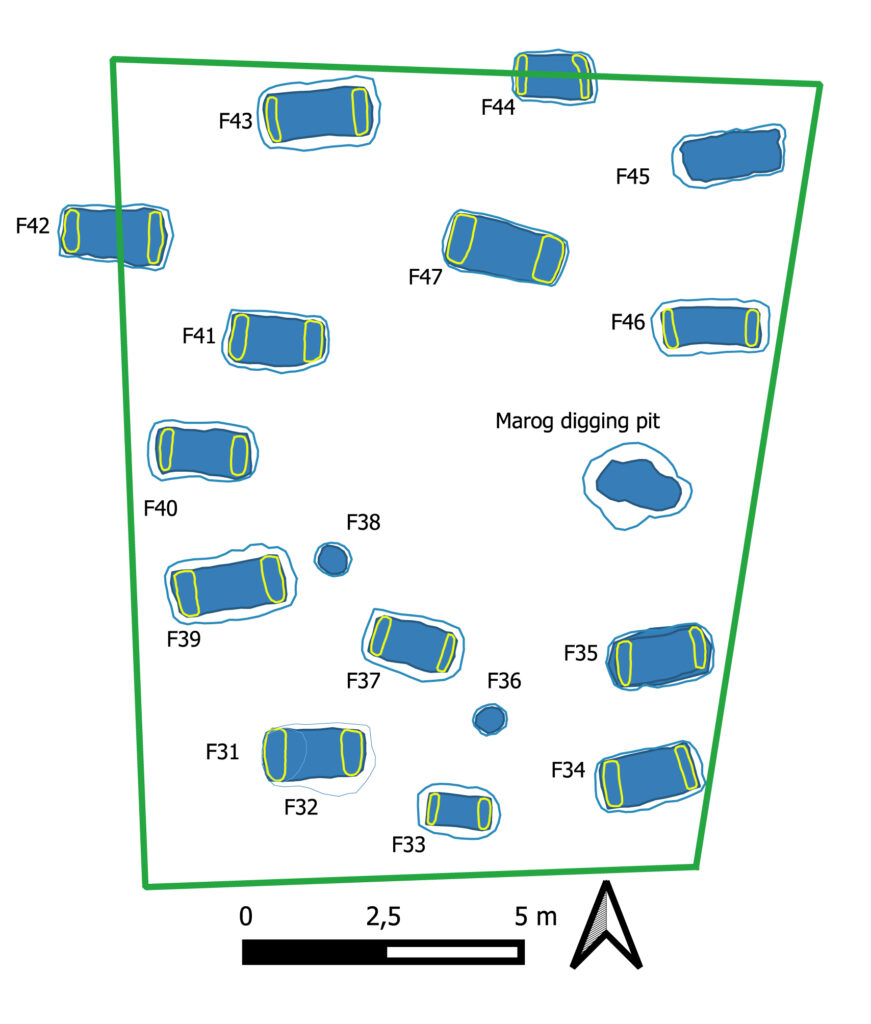

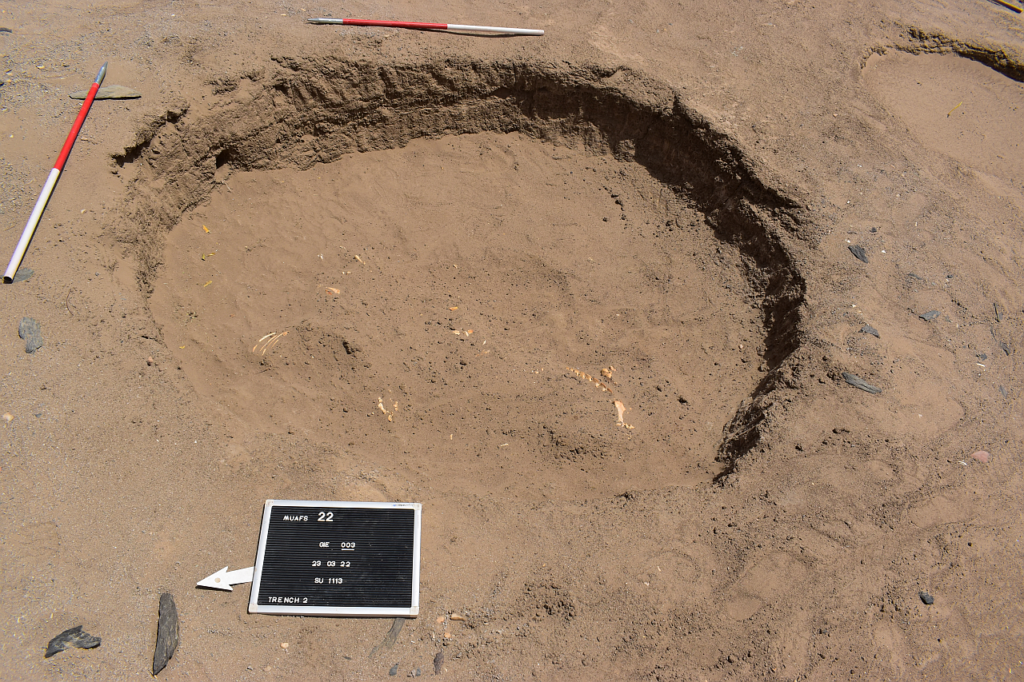

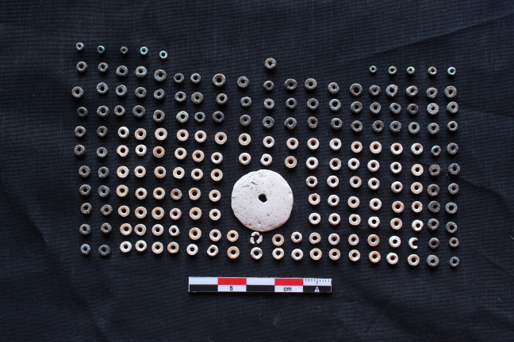

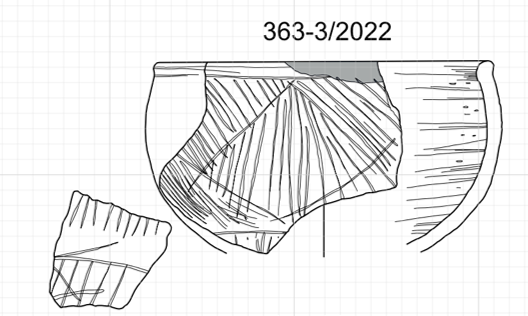

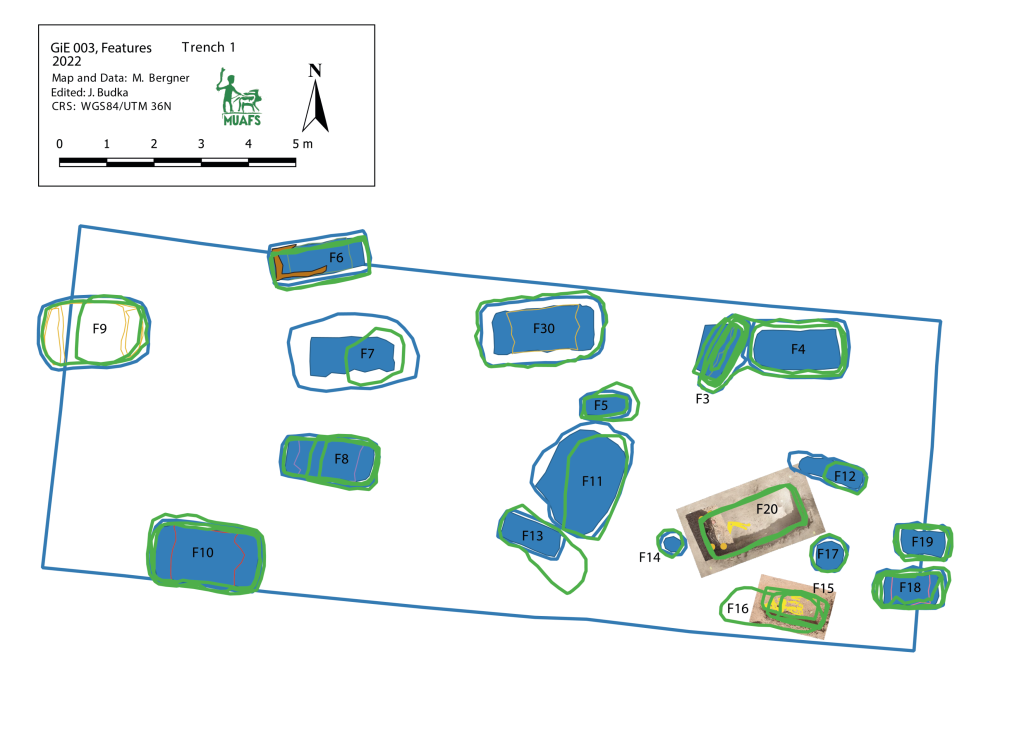

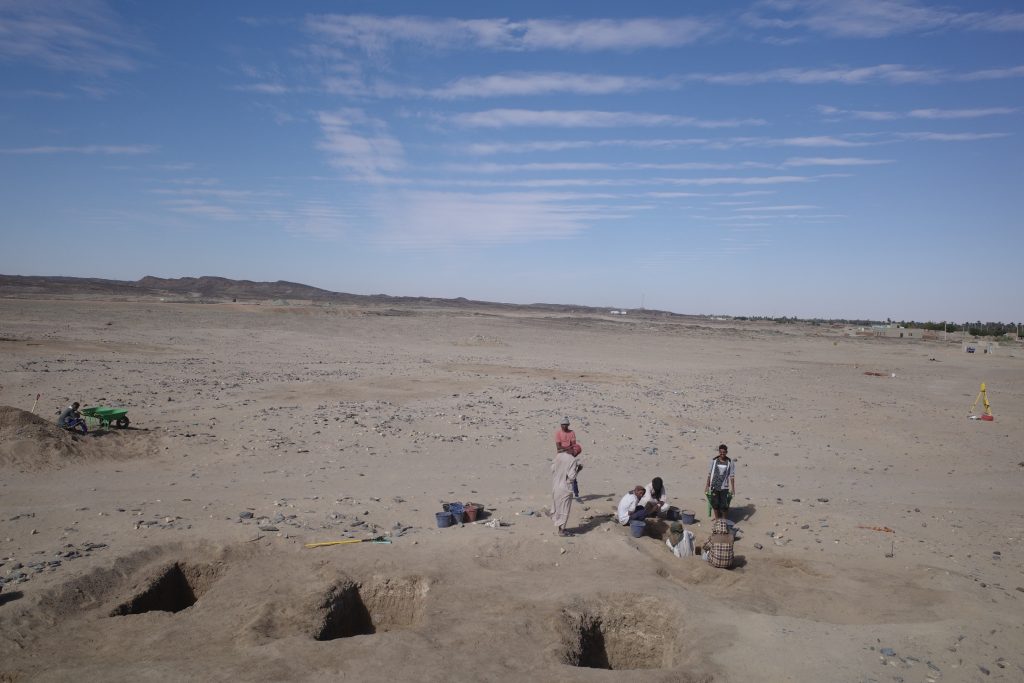

In our paper, Fig. 14 comprises a small assemblage of recently collected sherds from the fortified structure 2-S-43N, dating to the early 18th Dynasty, located in Attab West.

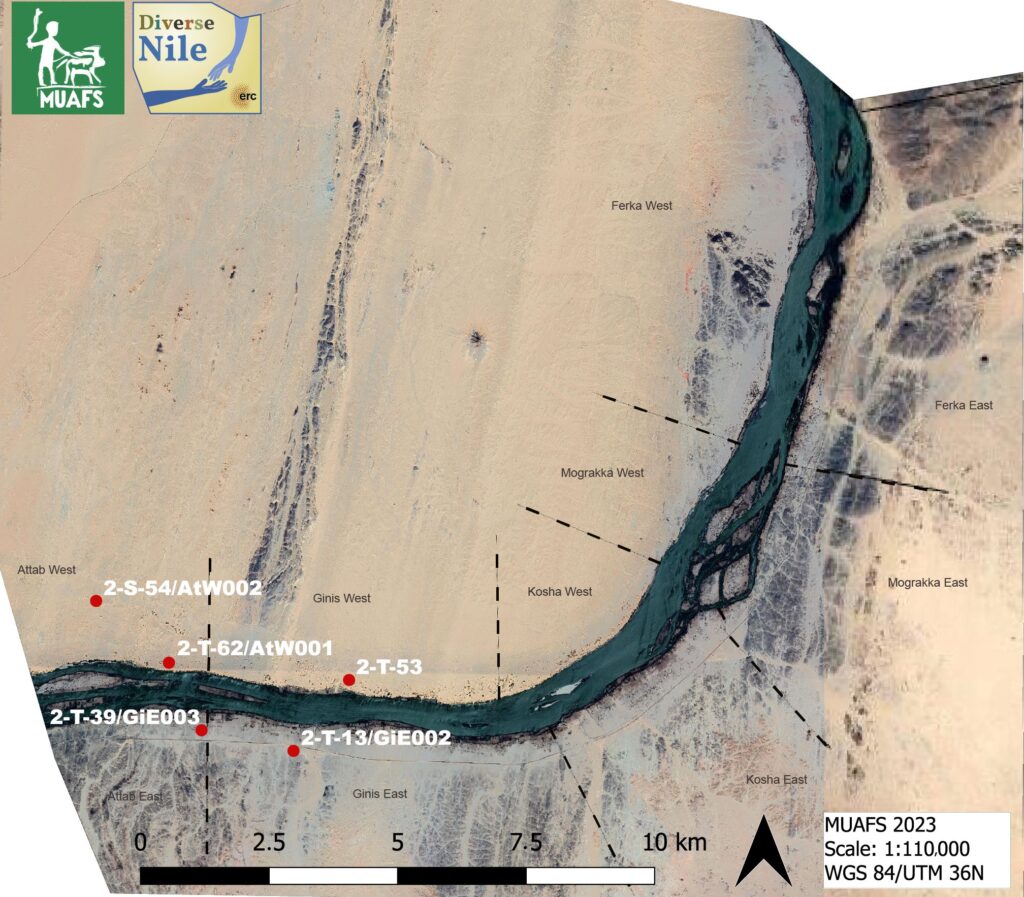

This site is of significant interest in the context of cultural entanglement, but it also serves to illustrate the pressing issues currently being faced in northern Sudan. It is fortunate that this region has thus far remained free from the direct impact of armed conflict; however, there has been a considerable loss of cultural heritage due to the expansion of gold mining activities. Evidence of this can be found at site 2-S-43N in the MUAFS concession, where a bulldozer has partially removed the structure, and across the entire west bank, extending from Attab to Ferka. Moreover, on the island of Sai, in close proximity, the repercussions of gold mining on archaeology are pronounced.

Turning once more to recent publications on pottery, it is with great pleasure that I announce the publication of an update concerning the Nubian ceramics found in House 55 in Elephantine, Egypt (Budka 2025b).

The study of the pottery from House 55 was initiated during the AcrossBorders project and was continued in 2024. The 2024 season focused on Nubian vessels and so-called hybrid vessels (labelled by Dietrich Raue as Medja-pots, imitating Pan-Grave style incised decoration on Egyptian style wheel-made globular bowls, Raue 2017). The combination of Nubian surface treatment with Egyptian production technique, utilising Egyptian Nile clay, is a distinctive characteristic of these vessels. The shapes exhibit notable similarities to Pan-Grave style cooking pots and globular bowls, while concurrently displaying closer affinities to Egyptian shapes, such as those seen in 17th Dynasty cooking pots.

The prevalence of Nubian pottery in House 55 is noteworthy, with a 17.3% representation in the diagnostic pieces and an average of 4.8% of the overall ceramic material (exceeding 5,500 individual Nubian sherds were documented). In conjunction with 67 hybrid vessels, the Nubian vessels account for 20% of the diagnostic ceramics subjected to detailed analysis from House 55. In the present report, I provided an update on the Nubian vessels.

In general, the Nubian vessels from House 55 are predominantly associated with the Pan-Grave horizon. However, there is also evidence of the presence of Classic Kerma forms and local variants. Drawing upon the extensive corpus from a singular context, Elephantine emerges as a preeminent site of Pan-Grave associated wares within Egyptian settlement contexts. This corpus encompasses a substantial array of black-topped fine wares, thereby complementing the pottery corpus attested from cemeteries (though it is imperative to note the existence of other findings in Egyptian settlements such as Edfu and Abydos; see de Souza 2019, 9).

This phenomenon can be conceptualised as ‚closing the circle‘: The presence of Pan-Grave horizon sherds has also been identified in the MUAFS concession, both in settlement and burial contexts. These include back-topped fine wares, vessels with incised decoration and presumed cooking vessels. This significant collection of pottery is currently being processed as part of the DiverseNile project. Knowledge of the material from Elephantine and also from Sai is of outstanding importance here, particularly in the context of investigating local patterns within a broader framework. The analysis of pottery provides a crucial avenue for reconstructing the lived experiences reflected in archaeological contexts, where aspects of interconnectivity, of seasonality and the combination and dynamics of various lifestyles need to be considered (Budka 2025b).

References:

Budka 2025a = Julia Budka, Nubian style pottery from the New Kingdom town of Sai Island, Old World: Journal of Ancient Africa and Eurasia (Special Issue) 5, 1‒81, https://doi.org/10.1163/26670755-04020011.

Budka 2025b = Julia Budka, 3.2 Nubian pottery from House 55 − an update, in: Martin Sählhof et al., Temples and Town of Elephantine. Final Report on the 52nd Season 2023/2024 by the German Archaeological Institute Cairo in Cooperation with the Swiss Institute for Architectural and Archaeological Research in Cairo, DAIK, 40-46, https://projectdb.dainst.org/fileadmin/Media/Projekte/2816/Dokumente/ELE-ASAE52-ENGLISH.pdf

Budka et al. 2025 = Julia Budka, Hassan Aglan & Chloë Ward, Reconstructing Contact Space Biographies in Sudan During the Bronze Age, Humans 5(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/humans5010001

D’Ercole et al. 2025 = Giulia D’Ercole, Julia Budka, Elena A.A. Garcea, More than one way to perform archaeometric analyses on pottery. Case studies from prehistoric to Bronze Age Sudan, Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, Volume 66, 105232, ISSN 2352-409X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2025.105232

de Souza 2019 = Aaron de Souza, New horizons: the Pan-Grave ceramic tradition in context, Middle Kingdom Studies 9 (London, 2019).

Raue 2017 = Dietrich Raue, Nubian pottery on Elephantine Island in the New Kingdom, in: Neal Spencer, Anna Stevens and Michaela Binder (eds.), Nubia in the New Kingdom: lived experience, pharaonic control and indigenous traditions (Leuven, 2017), 525-533.