I’m delighted to announce that a new publication is now available in open access. Me and my co-authors – Fabian Dellefant, Giulia D’Ercole, H. Albert Gilg, Rosemarie Klemm and Johannes H. Sterba – show how archaeometric techniques used as part of the DiverseNile Project can be used to investigate human-environment interactions in the Middle Nile during the Bronze Age.

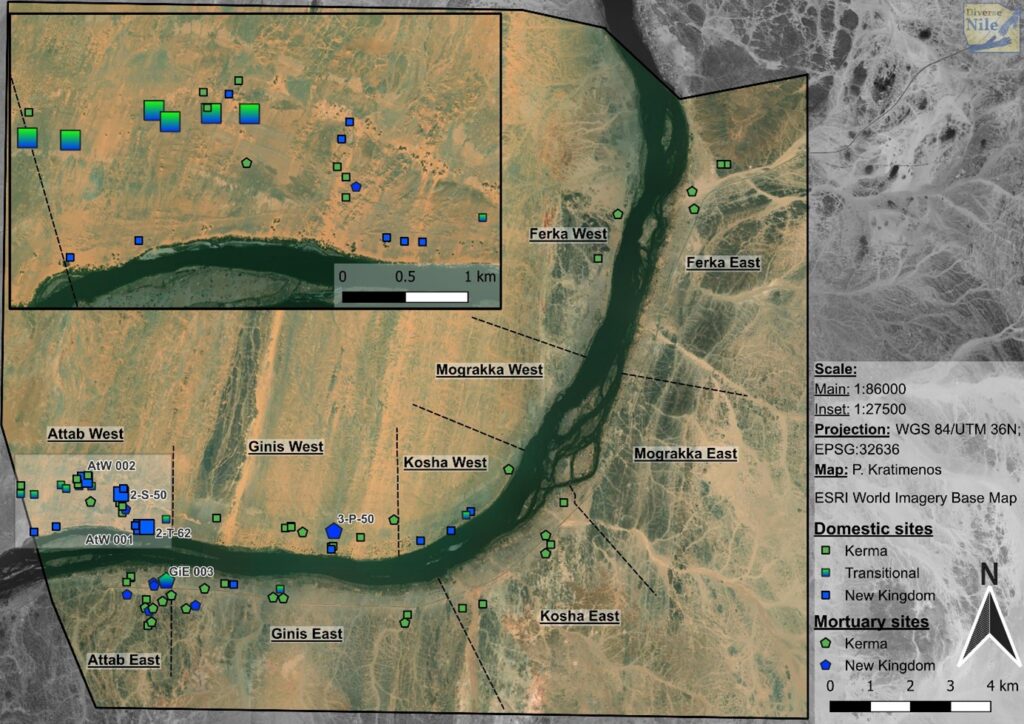

We present case studies from our recent investigation of landscape properties in the MUAFS concession area in northern Sudan, the Attab to Ferka region, and associated material remains. We also included some materials from Sai Island, the main urban site of this region. Our article looks at different ways to combine archaeology and geology, like taking rock samples and studying the composition of sandstones (see also an earlier blog post by Fabian). It also shows how these methods can be used to understand past landscapes and mobility patterns. We’re looking at the material culture, especially ceramics, in a bunch of different ways using a bunch of different scientific methods. We’re combining compositional bulk analysis (INAA) with mineralogical (XRD) and petrographic data via optical microscopy (OM) to check out the physical properties, where the ceramics came from and how they were made (you may want to check out an earlier blog post by Giulia). We’re also using Raman spectroscopy to see what temperatures the ceramics were fired at.

This paper shows how new developments in landscape archaeology and the archaeometry of material culture are helping us to understand the big ecological and social changes that happened in the Bronze Age Middle Nile. We think this combined analytical approach, which we’ve used in the Attab to Ferka region as an example, can also be successfully used in other regions around the world.

Full reference of the new publication:

Julia Budka, Fabian Dellefant, Giulia D’Ercole, H. Albert Gilg, Rosemarie Klemm & Johannes H. Sterba, Investigating human-environment interactions in the Middle Nile: The contribution of archaeometric techniques to understanding landscape use and social practices in Bronze Age Sudan, Egypt and the Levant 35, 2025, 101−134, https://austriaca.at/0xc1aa5572_0x00412ff6.pdf