Work on the fire dogs continues and remains mysterious. We recently carried out a „dry test series“ on the potential placement of the fire dogs, in which we considered different scenarios based on different amounts of fire dogs and different cooking pots. This allowed us to complete our experimental archaeology tests.

So far, no in situ finds of fire dogs are published from the New Kingdom, so all ideas about the use of fire dogs and their placement remain hypothetical. The best overview of the various hypotheses on the placement of the fire dogs can still be found in the 1989 article by David Aston (Aston 1989). His suggestion for the layout of fire dogs is still the most widespread today: three fire dogs with the „ears“ pointing downwards and the „noses“ pointing inward supporting a relatively large cooking pot placed on top of them (see the drawings, Aston 1989, 32 and plate 1). But were these exciting objects really used as he suggested?

So far, none of the known placement possibilities has really convinced us. As plausible as Aston’s model seems at first glance, it does not seem to make much sense on closer consideration. This is mainly due to the size ratio between the fire dogs and the cooking pots, which Aston himself has already acknowledged (Aston 1989, 32). In the 18th Dynasty in particular, the relative proportions between fire dogs and cooking pots are more extreme than Aston suggests. The pots are smaller than the pot used by Aston and the fire dogs are shorter. With such a size ratio, there is little room for a fire under or near the fire dogs and three fire dogs under one pot seem to be disproportional. In this case, it would make more sense to place the pot and fire dogs directly on the embers. However, there are no traces of smoke that would prove such a use. This problem can also be seen in Aston’s drawing, as the fire shown in the sketch appears far too small in relation to the fire dogs. The fire shown here is at most 5 cm high — a small ember for such a large pot.

The height of the fire would have varied based on the type of fuel used, for example wood fires require more space than fires with, for example, sheep or goat dung. The mixture of straw and animal dung documented in archaeological contexts may well represent a potential use as fuel (archaeological evidence e.g. from Amarna, Peet & Wooley 1923, 64, Moens and Weatherstrom 1988, 166-167). Experimental archaeological tests using animal dung showed that it could certainly be used for cooking. There are also parallels for this from ethnographic research (https://exarc.net/issue-2019-1/ea/question-fuel-cooking-ancient-egypt-and-sudan). However, the fires produced using dung are very difficult to maintain on such a small scale. It is therefore unlikely that the set-up suggested by Aston was used, especially in 18th Dynasty Sai, our main interest.

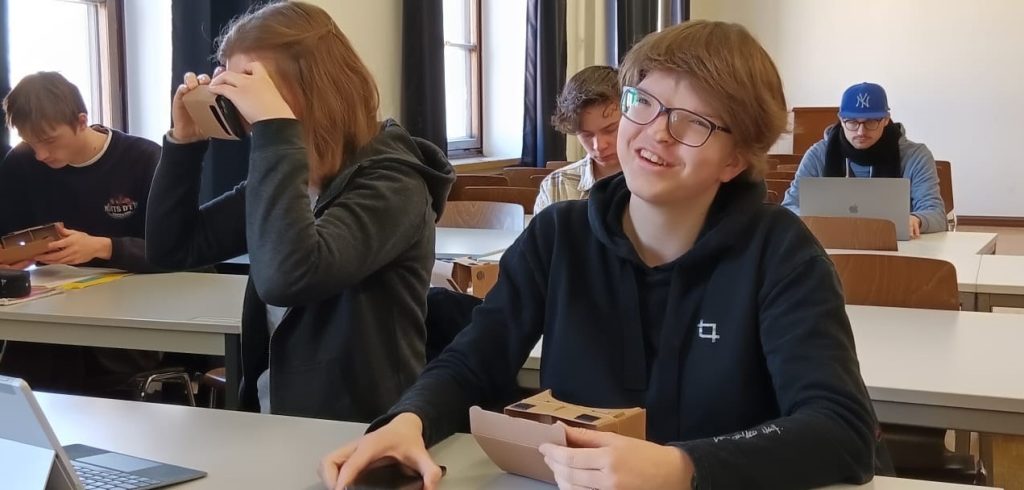

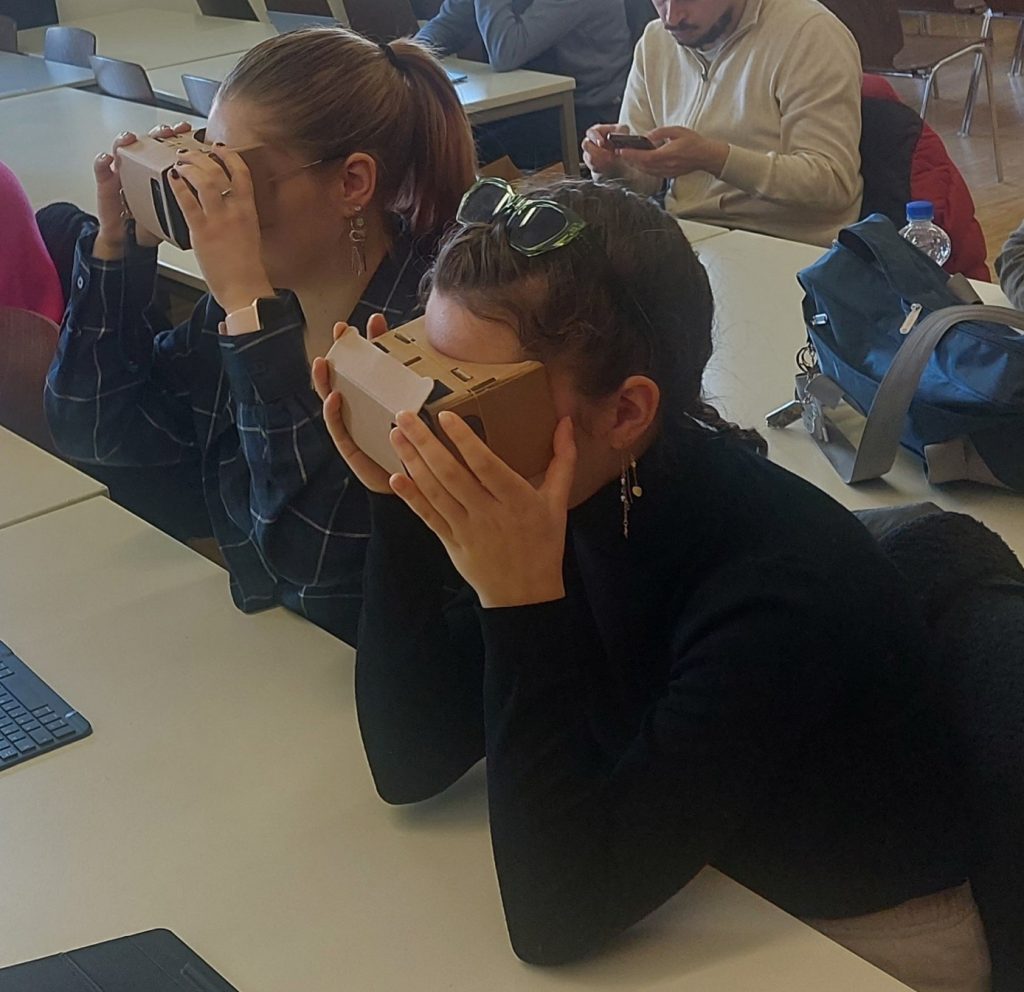

In order to try out different combinations of pots and fire dogs in a targeted manner and to make the experiments three-dimensionally comprehensible, we scanned the experiments as 3D models with the Scaniverse App (see https://scaniverse.com/).

With the help of Francesca Sperti, we have already been able to test several scenarios. We used our full-size replicas of the fire dogs produced in Asparn and tested three different pot variations:

- a replica of a typical pot from the New Kingdom

- a replica of a Nubian pot

- a carinated bowl, although it should be noted that this is not a proper replica

The Egyptian cooking pots are similar to the types known from Sai, Type A, and for the carination/pronounced shoulder see Type D, after Budka 2016, https://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/propylaeumdok/3868/1/Budka_Egyptian_cooking_pots_2016.pdf). Experiments with a full-size replica of a carinated bowl are still in progress.

Starting with Aston’s suggestion, we tried setting up 1, 2 or 3 fire dogs in different positions and directions with all pot shapes. It quickly became apparent that some of the fire dog placements we tried made it impossible to use certain cooking pots or made cooking and handling absolutely impossible. Other variations, on the other hand, are perfectly feasible. A clear favourite has also emerged for us, but this is still being tested with a better pot replica. So it remains exciting…!

References

Aston 1989= Aston, D., Ancient Egyptian „fire dogs“: a new interpretation. MDAIK 45 (1989), 27-32.

Budka 2016 = Budka, J., Egyptian Cooking Pots from the Pharaonic Town of Sai Island, Nubia, Bulletin de liaison de la céramique égyptienne 26, 2016, 285-295.

Moens and Wetterstrom 1988 = Moens, M.F. and Wetterstrom, W. The Agricultural Economy of an Old Kingdom Town in Egypt’s West Delta: Insights from the Plant Remains. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 47(3) (1988.), pp.159-173.

Peet and Wooley 1923 = Peet, T.E. and Woolley, C.L. 1923. The City of Akhenaten, Volume 1. Egypt Exploration Society, Excavation Memoir 38. London: Egypt Exploration Society.