Exams never end, not just for humans but even for archaeological artifacts.

Already before the Christmas break, I had happily returned to the lab, this time to prepare a new bunch of ceramic samples to undergo X-ray powder diffraction (XRPD) analysis. Thanks to a new cooperation with the TU München, and especially with Prof. H. A. Gilg (Chair of Engineering Geology) we decided in fact to complement our iNAA and OM analyses with this new laboratory methodology, with the aim of expanding our knowledge on the composition, provenance and technology of production of our Nile clay samples. All in all, we preliminary selected 30 ceramic specimens, among Nubian- and Egyptian-style sherds from the 2022 and 2023 excavated sites at Attab West and Ginis East. To this sample, we added a replica in modern Nubian (from Abri) Nile clay manufactured by us during our last workshop in Asparn.

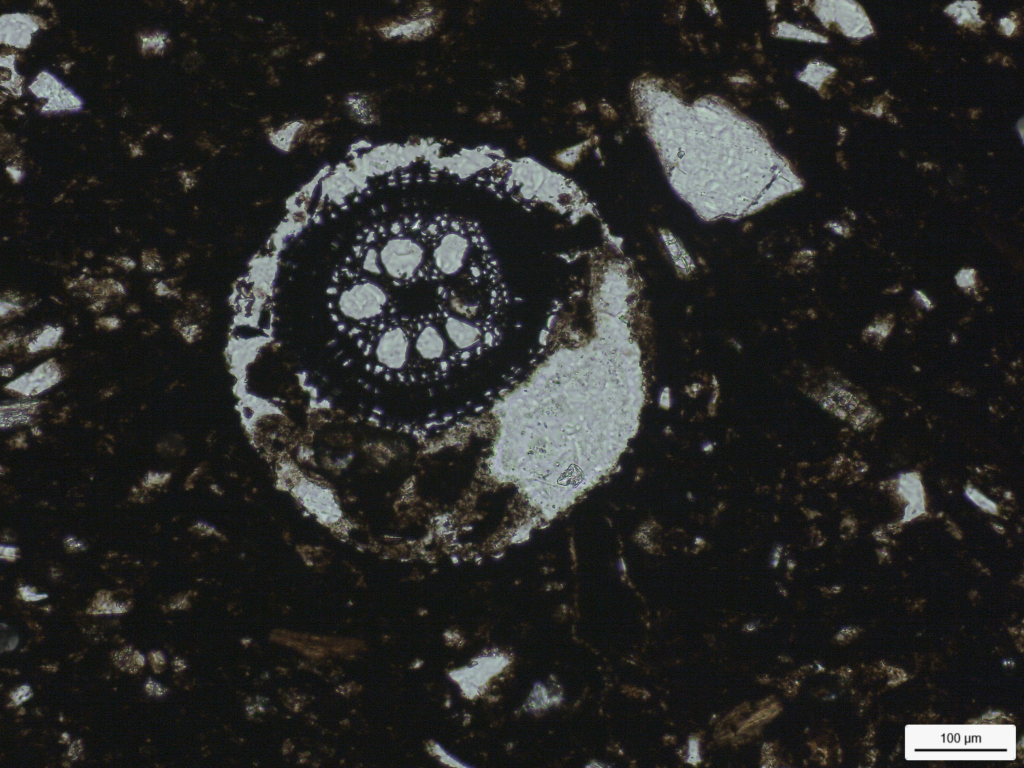

Generally speaking, X-ray powder diffraction analysis is a well consolidated analytical technique used in the field of archaeometry and ceramic technology to determine the mineral phases present in the pastes, including those clay phases which are typically not visible under the microscope. This technique also provides information on the firing process the pottery went through. Certain minerals (e.g., calcite as one of the most known) can in fact degrade, disappear or be altered at given temperatures because the crystalline structure collapses through the process of dehydroxylation (Magetti 1982; Rice 1987). The analysis itself based on the phenomenon of diffraction of electromagnetic radiation, by exploiting the fact that X-rays falling on crystalline planes in minerals are reflected at varying angles (Velde and Druc 1999; Quin 2013). Hence, each mineral type will produce a characteristic X-ray diffraction spectrum with diagnostic peaks placed at given angular distances (expressed in degrees 2θ), allowing the qualitative identification of the minerals present within the ceramic sample. The heigh of those picks permits otherwise a semi-quantitative estimation of the ratios in which minerals are more or less represented.

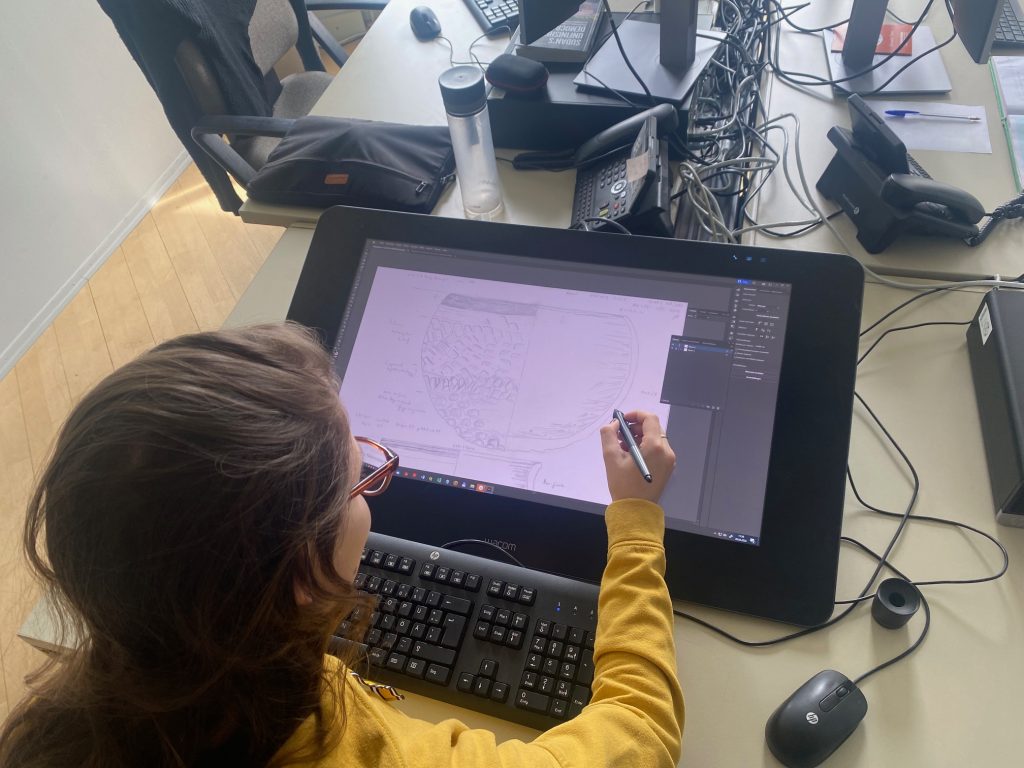

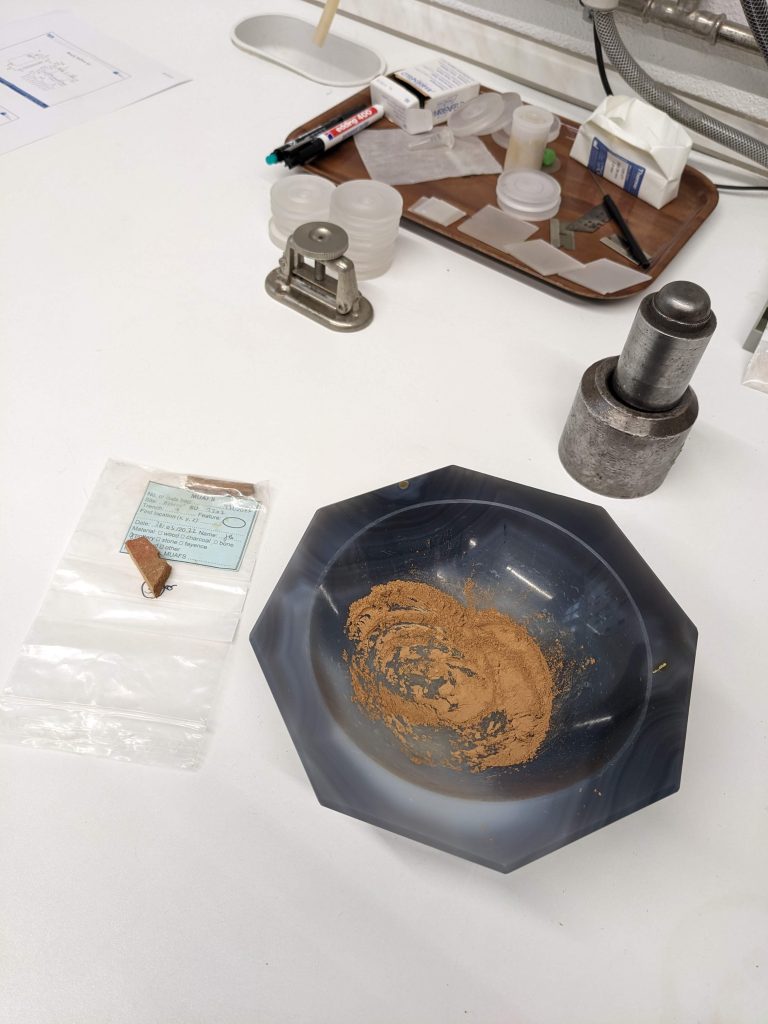

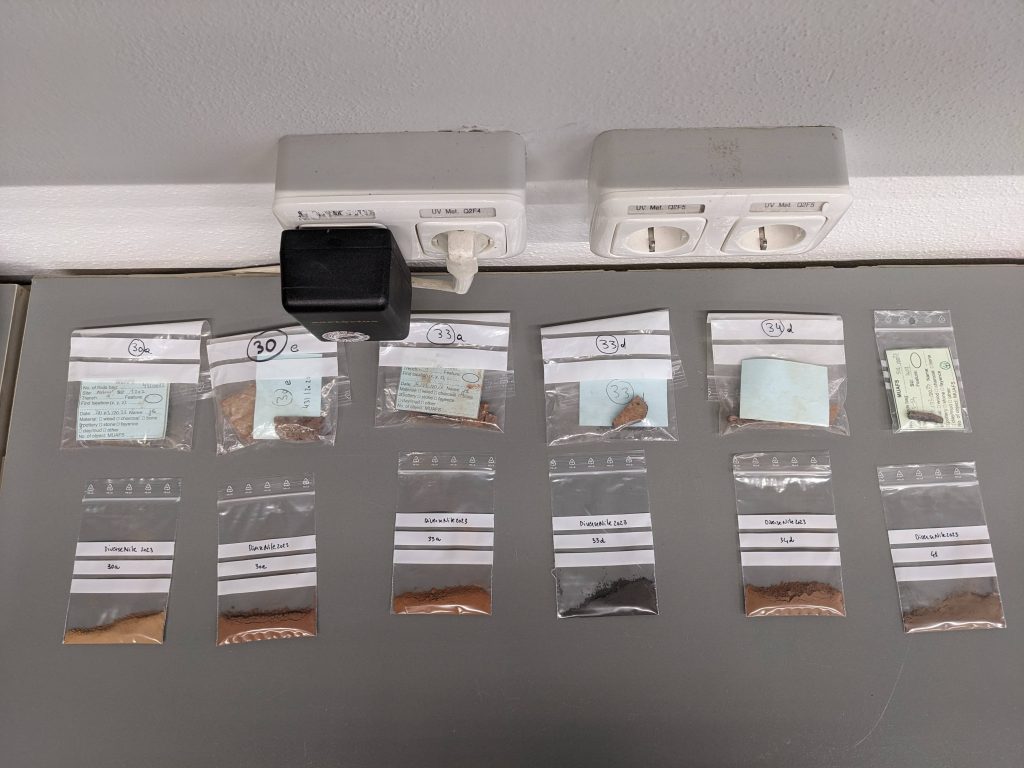

Sample preparation is pretty much straightforward although partially destructive. The procedure requires that a tiny portion of the sherd be ground up (about 1g of powder) by hands with an agate mortar and a pestle, alike those used for iNAA, pressed in the mounting smear slide, and then put into the instrument. Proper pulverization and homogenization are crucial to achieve highly quality XRD data.

The sample needs to be as representative of the ceramic sherd as possible – for this reason, it is sometimes advisable to grind a larger quantity of powder and above all finely ground so as to prevent larger crystals (e.g., coarse quartz grains) from interfering with the measurement. This latter can be carried out with different timing and levels of accuracy depending on whether one wants only a rough semi-quantitative estimate of the mineral phases in the sample or more accurate information.

In performing XRD analysis, our main archaeological questions were the following:

- Can we recognize the use of different clay raw materials for the different sites/locations (e.g., Attab, Ginis…);

- Can we differentiate between Nubian- (also Pan-Grave) vs. Egyptian-style samples;

- Can we differentiate between the different ceramic types and wares;

- Can we demonstrate the intentional addition of tempers (calcite and/or quartz and/or feldspar and/or mica) in particular samples?

- Can we know more about the firing process (i.e., firing temperatures) the ceramics went through?

Currently, together with Prof. Gilg, we just started to interpret the results of the first diffractograms. The data are not always straightforward to read and the differences between the various samples look sometimes very subtle – on the other hand our Nile clay samples have used us to significant challenges for many years already!

Preliminary, we can say that, based on the diagnostic mineral phases in the various spectra, it was possible to recognise four distinct groups or types of samples. These groups do not depend on the main phases (quartz or feldspar) as these are present in nearly homogenous amounts in all samples. Rather, some differences can be spotted in the clay minerals. Whether these latter can be ascribed to different clay sources, preparation recipes, or eventually the pot production (i.e., firing) has yet to be fully assessed.

References

Maggetti, M. 1982. Phase Analysis and its Significance for Technology and Origin. In J. S. Olin and A. D. Franklin (eds.), Archaeological Ceramics: 121−133. Washington, Smithsonian Institution Press.

Quinn, P. S. 2013. Ceramic Petrography: The Interpretation of Archaeological Pottery & Related Artefacts in Thin Section. Oxford, Archaeopress.

Rice, P. M. 1987. Pottery analysis. A sourcebook. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Velde, B. and Druc, I. C. 1999. Archaeological Ceramic Material. Origin and Utilization. Berlin Heidelberg, Springer-Verlag.