Week 5 of our 2023 field season just flew by, especially because of several very disturbing incidents.

On the positive side, we managed to close excavations at site AtW 001, postponed further exploration of Vila site 2-S-54 to next year and made good progress in the Kerma cemetery GiE 003.

AtW 001 will require much post-excavation work – we documented several still standing mud brick walls, there were clearly several phases of building and use. Chloe Ward who did an excellent job this season has already arrived back in Munich and is busy finalizing the stratigraphy and feature description as well as other details from her desk back home.

Most importantly, we managed to reach the same ashy layer on the alluvial surface like in 2022. It is now also clear that apart from a slight natural slope, most of the mound-like appearance of site AtW 001 is actually composed of settlement debris and especially mud brick debris in several layers.

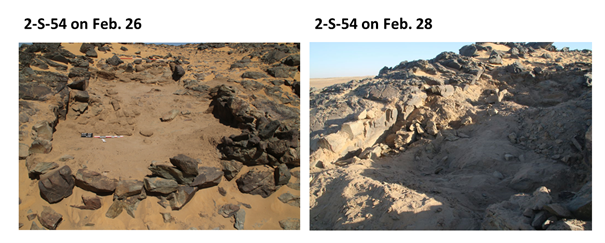

Excavations at Vila site 2-S-54 came to an unexpected stop – the material culture of the mud brick and stone building is really intriguing and currently being studied by Giulia D’Ercole and myself. Giulia arrived this week and already prepared all the samples from site 2-S-54 we will export for iNAA analysis in order to investigate the provenience of Nile clay wares (see earlier posts by Giulia on this subject, e.g. https://www.sudansurvey.gwi.uni-muenchen.de/index.php/2020/12/22/where-are-you-from-a-diverse-material-perspective-on-this-common-tricky-question/). Of course, a substantial part of our 2023 samples will come from site AtW 001, but here I am still busy reconstructing the large number of complete vessels. More than 10.000 sherds need to be checked for matching pieces and this clearly takes a while.

Finally, much progress was made in the Kerma cemetery GiE 003, where work in Trench 3 was concluded (and yielded a total of 14 new Classic Kerma burial pits, closely resembling our results from 2022) and excavation in Trench 4 is still ongoing. All tombs have been looted in antiquity, most probably in Medieval times, but there are still substantial remains of material culture, especially pottery, beads and remains of wooden funerary beds.

One of the most remarkable finds of this season is a small ivory bracelet from Tomb 33 in Trench 3. It was clearly used for a long time, was broken at a certain point, and then repaired by means of repairing holes – this is how we found it deposited in the burial pit. An intriguing object in many respects!

Jose M.A. Gomez, Huda Magzoub, Sofia Patrevita and our team of local workmen got new reinforcement this week: two students from Al-Neelain University in Khartoum have joint us. Tasabeh Obaid Hassan and Mohamed Abdeldaim Khairi Ibrahim have been already extremely helpful at the excavation in the Kerma cemetery and for example very quickly learned to measure targets and outlines of stratigraphic units with the totalstation.

I am very grateful to all team members and looking much forward to the results of week 6!