Still on the traces of Nubian goldsmiths, I would like to share some thoughts about a fascinating type and a goldsmith technique common in modern jewellery but already used and widespread in Kerma time: the gold bezel.

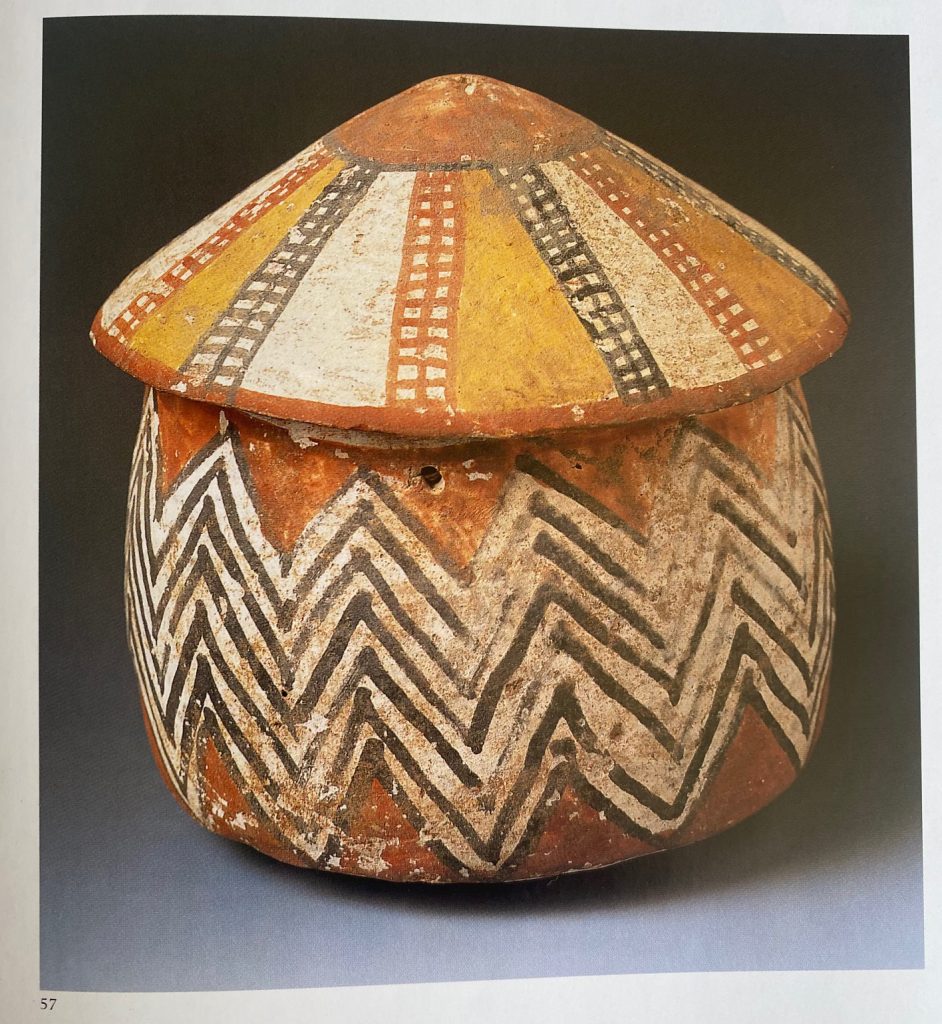

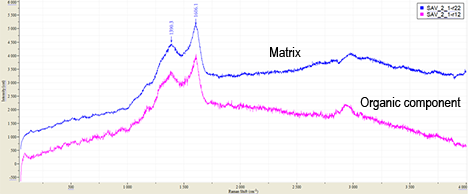

Significant for the study of local gold working in Nubia is a scarab necklace with gold bezel from tomb K1053 at Kerma (Fig. 1), dating to the Classic Kerma Period (c. 1700-1550 BCE). This string is composed of carnelian and amethyst beads of different shapes and typologies and a beautiful blue-glazed steatite scarab pendant set in an accurate gold bezel. According to Markowitz, the gold bezel was added and created by Nubian goldsmiths to emphasize the high rank and role of its owner (Markowitz, Doxey, 2014). The elite individual (Body D) of the Classic Kerman subsidiary grave K1053 was a Kerman woman buried with typical personal adornments, such as a silver headdress, a leather skirt with silver beaded drawstring, a necklace of blue-glazed crystal ball beads, a double set of gold armlets and bracelets on her upper and lower arms and this fascinating gold bezel scarab necklace held in her hand (Minor, 2018) (Fig. 2).

Other interesting gold bezel scarabs are attested from Kerma: a blue-glazed steatite scarab back covered with gold plate (K X B, western part, Body XK); a scarab with gold back-cover and two carnelian sphinxes amulets (K 439, Body B); an uninscribed amethyst scarab uninscribed with a gold mounting (K IV B, Body J) (Reisner, 1923, pp. 198-228-305).

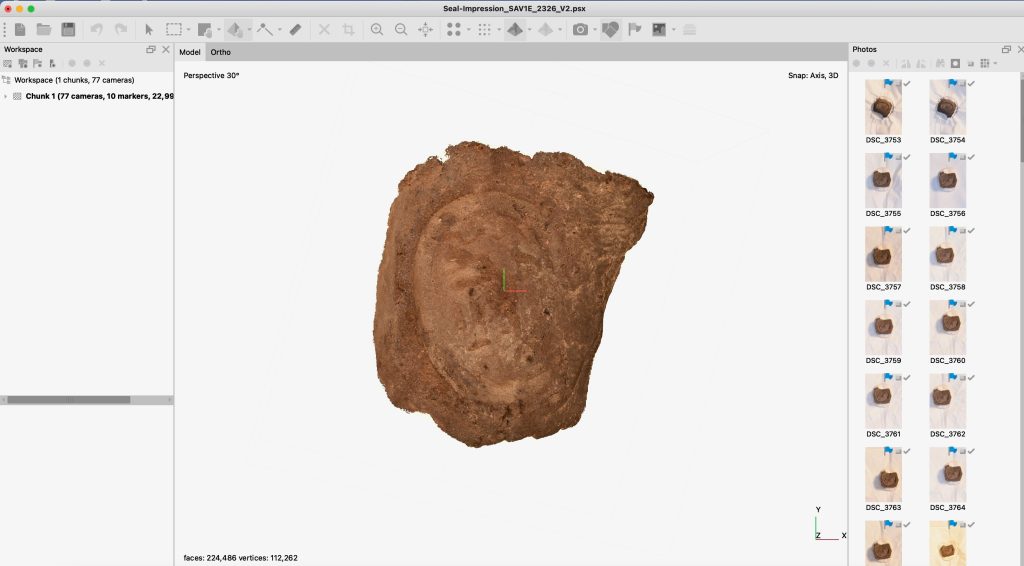

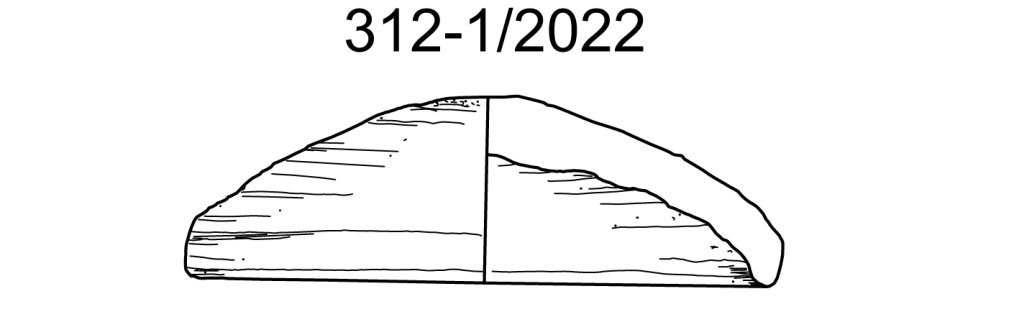

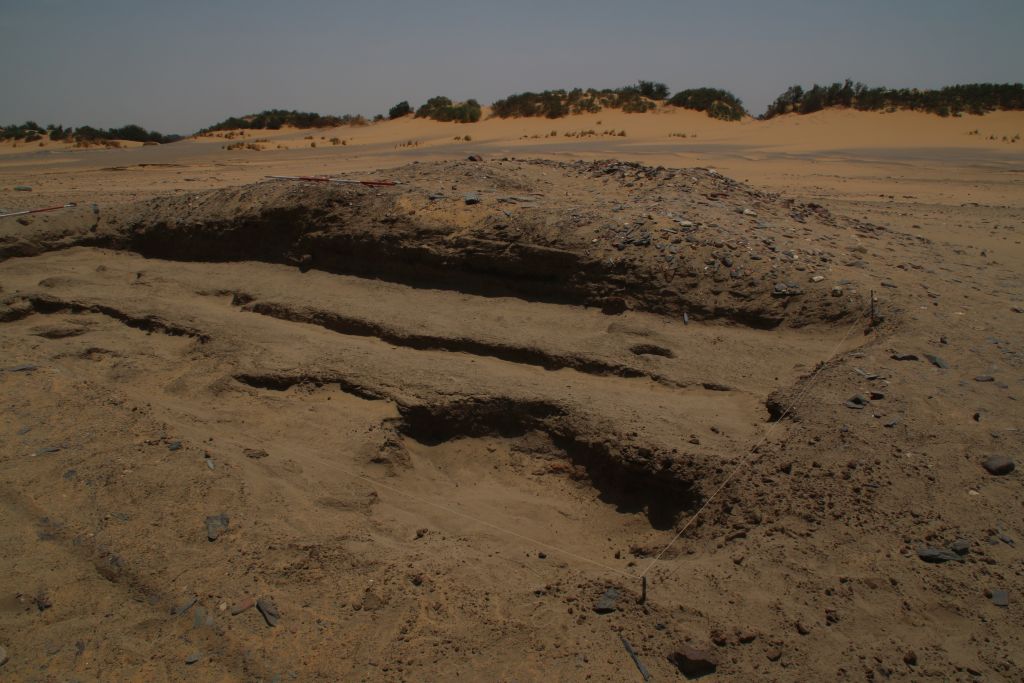

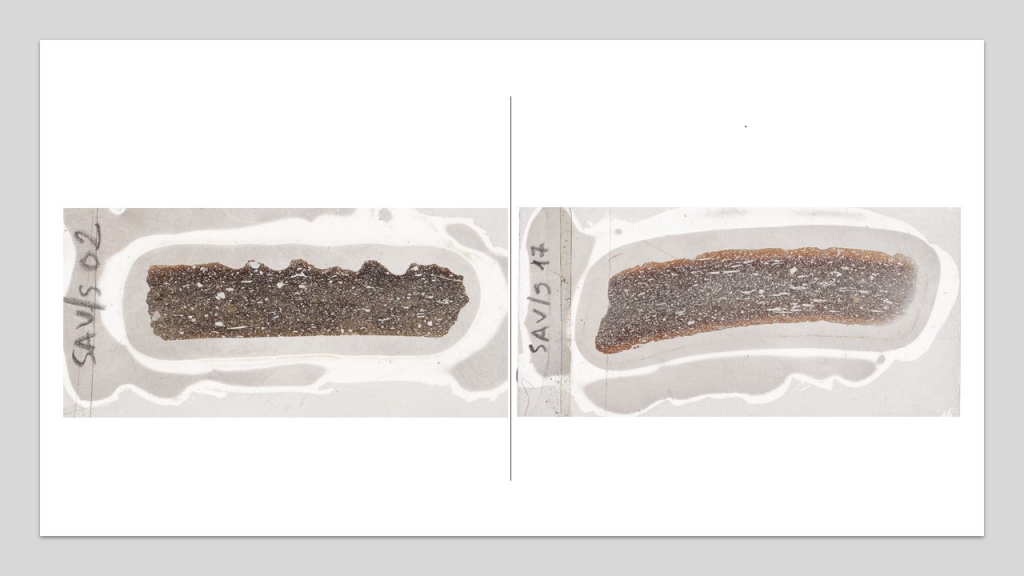

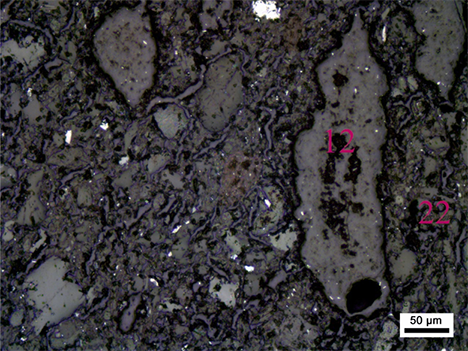

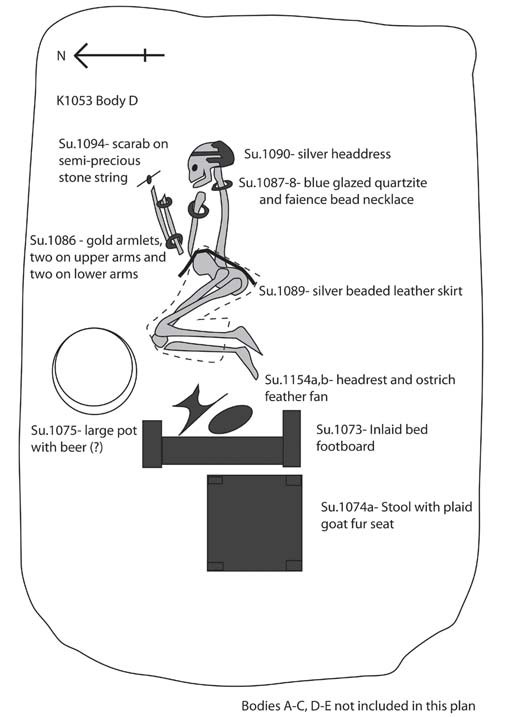

Really fascinating traces of a specific typology of gold bezel come from the heart scarab (SAC5 349) of the goldsmith Khnummose, found with his body in the Tomb 26 (Chamber 6) at Sai Island (New Kingdom, mid-18th Dynasty) (Budka, 2021). This inscribed serpentinite heart scarab, discovered by our PI Julia Budka and her AcrossBorders’ Team (read here more on this extraordinary discovery!), was found in situ with gold foil remains. During the process of cleaning, fragile strips of gold were found close to the head of the scarab and only one piece was clearly attached around the base, suggesting the presence of a bezel, most likely made with a very fine gold leaf. Indeed, the largest gold fragment has a large hole pierced through it, probably connected to the holes of the scarab (Budka, 2021) (Fig. 3).

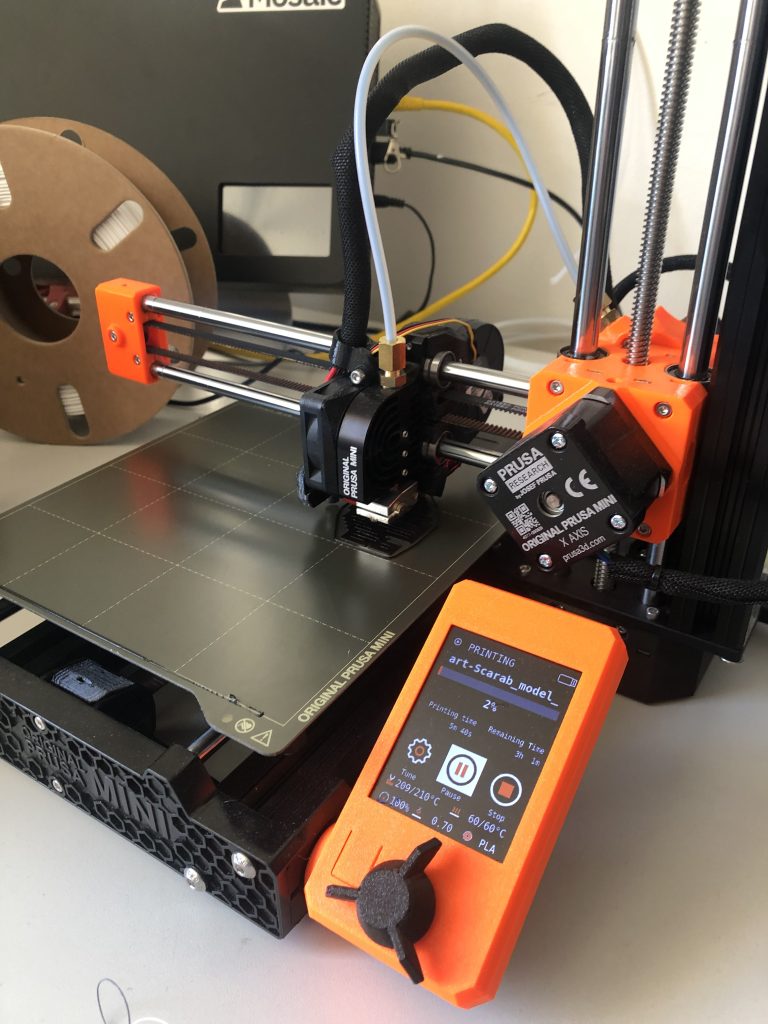

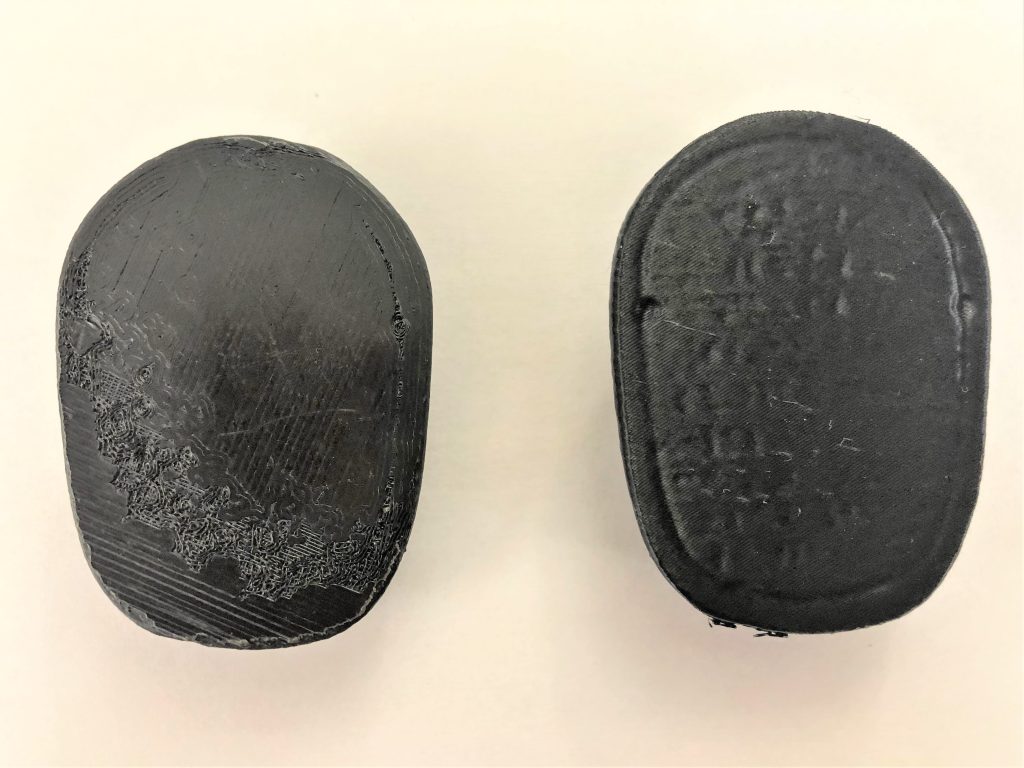

…and if you missed Kate’s post on the 3D reproduction of this heart scarab, hurry up and read it! https://www.sudansurvey.gwi.uni-muenchen.de/index.php/2022/12/06/diverseniles-explorations-in-3d-printing-ancient-nubian-objects/

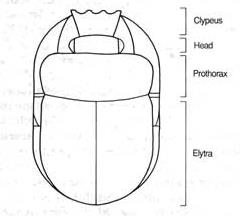

The heart scarabs were occasionally enclosed in gold mountings in Egyptian jewellery during the New Kingdom, manufactured through the use of two main techniques: the lost wax or the welding of two separate pieces of a gold sheet (Andrews, 1994; Schäfer, Möller, Schubart, 1910). Both are still used in modern jewellery; the second technique allows the creation of a particular type of bezel exclusively used for heart scarabs. It’s a gold bezel that not only holds the base of the scarab but is characterized by a T-cage that supports the funerary amulet along the part of the scarab body called elytra (the closed wings), following their shape (Fig. 4). These gold bezel heart scarabs were hung from a gold chain or tourques through a suspension loop welded on the upper part of the bezel or the perforated scarab and bezel. Excellent examples are dated to the 18th Dynasty: the serpentinite and gold heart scarab of Neferkhawet (MMA 729), early 18th Dynasty, Thebes, Asasif (Fig. 5); the green schist and gold heart scarab of Maruta (Tomb of the Three Foreign Wives of Thutmose III), 18th Dynasty, Thebes, Wadi Gabbanat el-Qurud (Fig. 6); the green jasper and gold heart scarab of Djehuty, 18th Dynasty, Saqqara (Andrews, 1994; Budka, 2021).

Coming back to Tomb 26, the family tomb of goldsmith Khnummose, there was also an exceptional steatite scarab ring in gold and silver (SAC5 388) of the 18th Dynasty (Budka, 2021) (Fig. 7). It was discovered with the female Individual 324. Among her bodily adornment, there was also an interesting necklace with carnelian and bone crocodile pendants and beads in different materials, such as gold (exactly 180 beads!). The finger ring has a heavy gold setting, most likely made by wax carving and lost wax techniques. The shank of the ring is in silver, while its small domed caps are gilded. The thin gold wire threads through the scarab, the gold bezel and the gilded caps twisting on both sides of the ring and finally fixed in small holes drilled in the silver shank (for an accurate description of these and other beautiful finds from the Tomb 26 do not forget you can find the complete book here https://www.sidestone.com/books/tomb-26-on-sai-island).

The gold bezel seems to be a distinctive feature of the Nubian jewellery, but additionally, these bezels from Sai come from the tomb of a local goldsmith and his family. Khnummose held two titles: “goldworker/goldsmith” and “overseer of goldworkers” (Auenmüller, 2020; Budka, 2021).

Even if with a less sophisticated mounting than the typology of the gold and silver ring from the Tomb 26, another intriguing comparison comes from Aniba and two scarab rings (n.34, n.36; see Budka, 2021, 212). The moving bezel is fixed to the ring by a thin metal wire that passes through the scarab, twisting on both sides of the ring. The ring n.34 is in silver, while the n.36 is in bronze (Steindorff, 1937, 111, pl. 57, nos. 34 and 36).

During the New Kingdom, the scarab mounted in gold remained the most common design for finger rings (Wilkinson, 1971). This technique, the mounting of the gold bezel, characterized by different methods (Maryon, 1971), appears already among the “innovations” of the Middle Kingdom goldsmithing. The first scarab rings were made from a single wire. From the 13th Dynasty the ends of the ring were equipped with grommets through which passed the wire that held the perforated stone. However, friction between the stone and the metal frequently led to shredding, therefore goldsmiths started to create “a metal protection” for the stone: the bezel (Schäfer, Möller, Schubart, 1910).

It has been suggested that the Egyptians adopted this goldsmithing typology and technique from a foreign people, perhaps from the Mycenaean culture where these rings were used (Schäfer, Möller, Schubart, 1910). However, the gold bezels found at Kerma, used as pendants/amulets rather than rings, but also the later examples from Sai, could attest to a local Nubian typology and manufacturing, the possible influence or technology transfer between Egypt and Nubia and the use of different techniques and specific tools already during Kerma times and through the New Kingdom.

References

Andrews C., 1994, Amulets of Ancient Egypt, British Museum Press, London.

Auenmüller J., 2020, Nubisches Gold und ägyptische Präsenz: Pharaonische Goldgewinnung in der Nubischen Wüste, in: M. Kasper, R. Rollinger, A. Rudigier& K. Ruffing (eds.), Wirtschaften in den Bergen. Von Bergleuten, Hirten, Bauern, Künstlern, Händlern und Unternehmern, Montafoner Gipfeltreffen 4, Wien, 37–54.

Budka J., 2021, Tomb 26 on Sai Island. A New Kingdom elite tomb and its relevance for Sai and Beyond, Sidestone Press, Leiden.

Markowitz Y., Doxey D. M., 2014, Jewels of Ancient Nubia, MFA Publications, Boston.

Maryon H., 1971, Metalwork & Enamelling, Dover Publications Inc, New York.

Minor E., 2018, Decolonizing Reisner: a case study of a Classic Kerma female burial for reinterpreting Early Nubian archaeological collections through digital archival resources, Nubian Archaeology in the XXIST century, Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conferencefor Nubian Studies, Neuchâtel, 1st-6th September 2014, PEETERS, LEUVEN – PARIS – BRISTOL, CT, 251–262.

Reisner G.A., 1923, Excavations at Kerma, Parts I-III,Joint Egyptian Expedition of Harvard University and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Harvard African Studies 5, Cambridge.

Schäfer H., Möller G., Schubart W., 1910, Äegyptische Goldschmiedearbeiten, Verlag Von Karl Curtius, Berlin.

Steindorff G., 1937, Aniba. Zweiter Band. Service des Antiquites de l’Egypte. Mission archeologique de Nubie 1929-1934. Glückstadt: Augustin.

Wilkinson A., 1971, Ancient Egyptian Jewellery, London.