After a very successful Ankh-Hor Project season in Luxor as well as a wonderful participation in the South Asasif Conservation Project, I arrived in Cairo yesterday. I have the pleasure to spend four more days here in this splendid city before heading back to Germany. This is not just some leisure time after the intense excavations, but today is the opening of the international conference „Gateway to Africa: Cultural Exchanges across the Cataracts (from Prehistory to the Mameluk era)“.

The event is hosted at the Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale du Caire and was organised by Valentina Gasperini, Gihane Zaki and Giuseppe Cecere. I am very thankful to the organisers for giving me the opportunity to present the DiverseNile project in this context. I will be talking about “Cross-cultural dynamics in the Attab to Ferka region: reconstructing Middle Nile contact space biographies in the Late Bronze Age.”

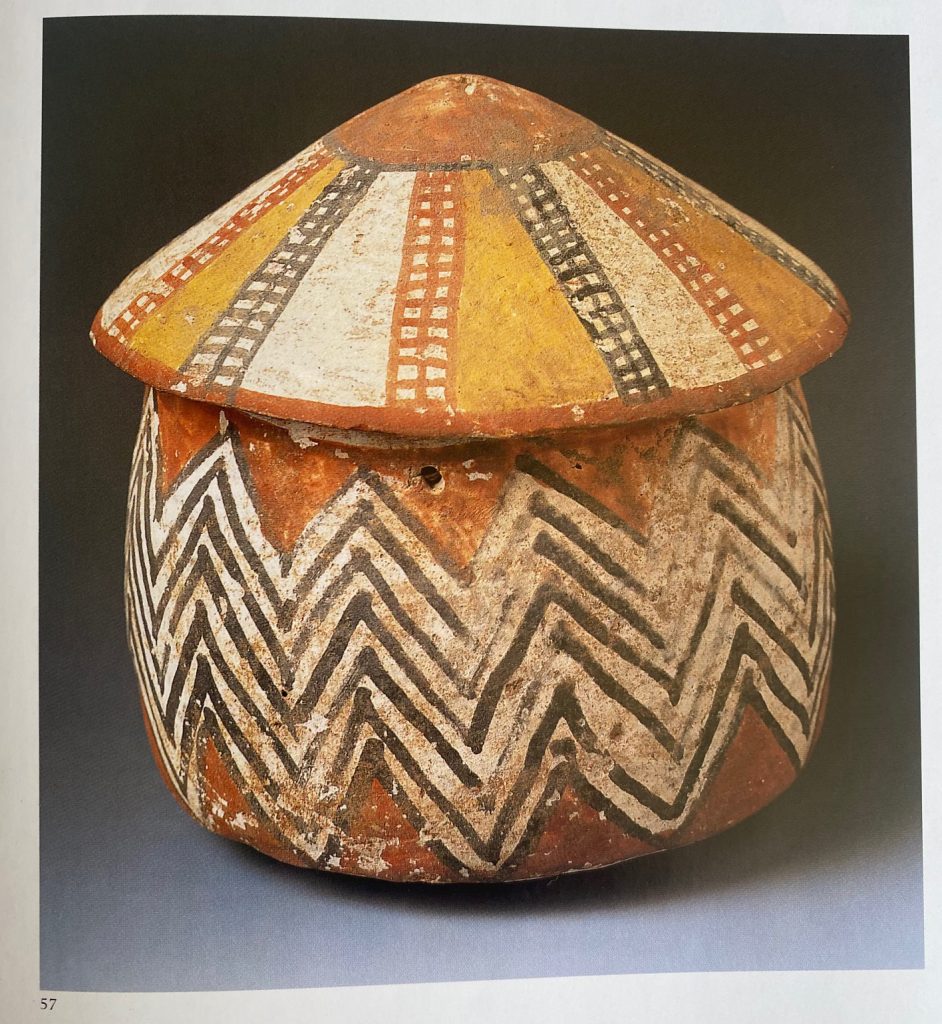

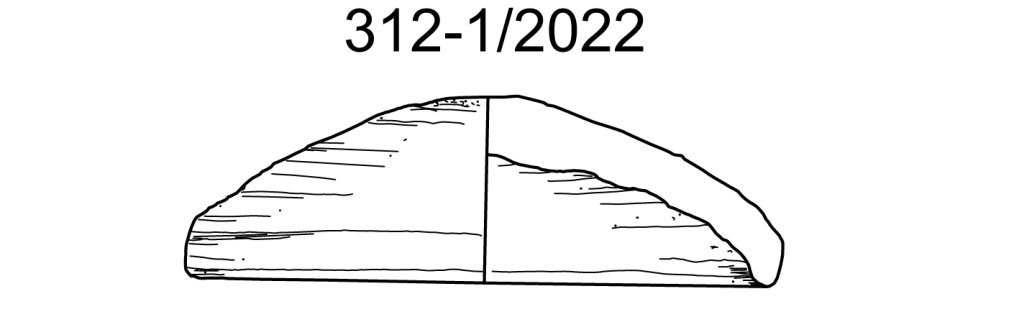

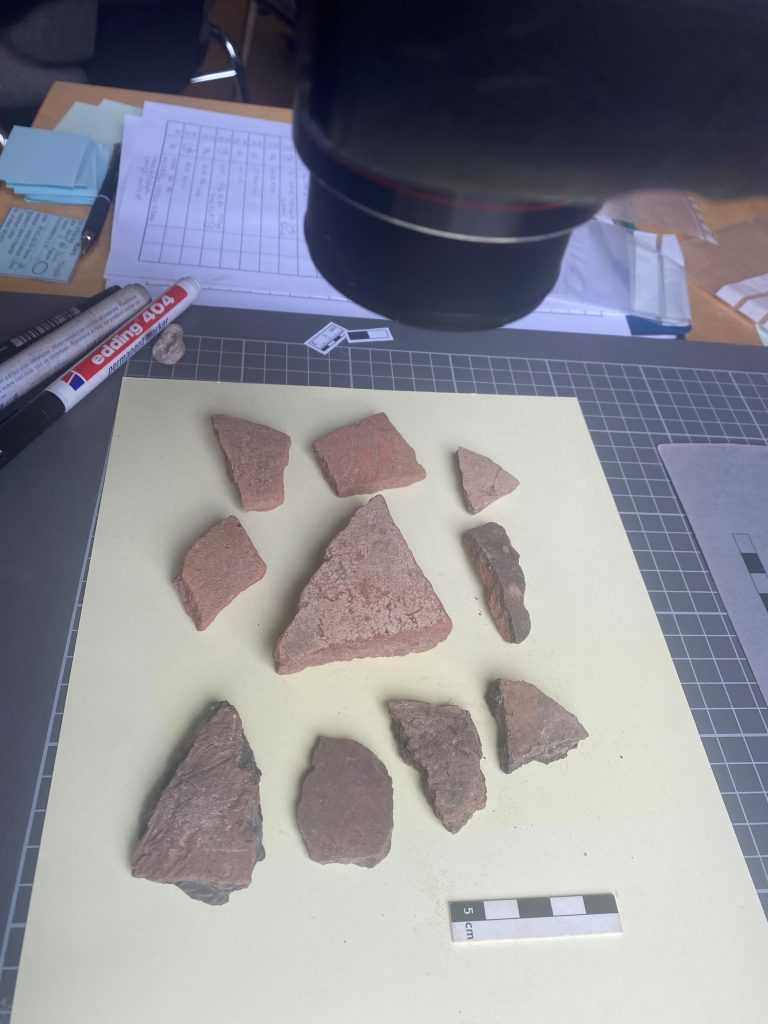

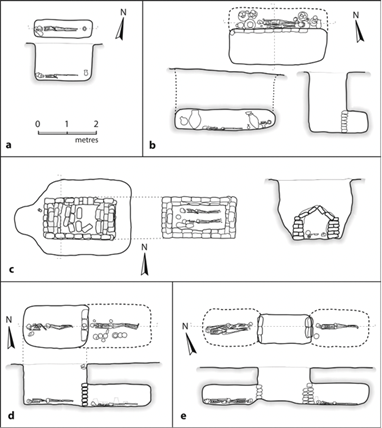

I will present the material evidence for complex encounters of various Egyptian and Nubian groups in the region of Attab to Ferka in the hinterland of the New Kingdom urban sites of Sai Island and Amara West. The rich archaeological record of this part of the Middle Nile reveals new insights into the ancient dynamics of social spaces. I will give some case studies from both settlements and cemeteries and will focus on the intriguing domestic site AtW 001 and the Kerma cemetery GiE 003.

I will discuss our recent idea that the material culture and evidence for past activities at such sites suggest complex intersecting and overlapping networks of skilled practices, for example for pottery production – see here also the latest blog post by Giulia D’Ercole.

I will also argue that the evidence from cemetery GiE 003 supports the general picture emerging regarding cultural exchanges in the Kerma empire. There was no single Kerman cultural input to interactions with the Hyksos, Egyptians and nomadic people but we must consider various hierarchical local responses determined by different communities’ ability to consume, shaping what can be called marginal communities in the Kerma state (cf. Lemos & Budka 2021 and most recently Walsh 2022). We are making very good progress in understanding the communities in the Attab to Ferka region and I am much looking forward to the next days and the possibility to discuss cultural exchanges throughout the centuries in the Nile Valley (and beyond) with all the participants of this exciting IFAO conference.

References

Lemos and Budka 2021 = Lemos, R. and Budka, J., Alternatives to colonization and marginal identities in New Kingdom colonial Nubia (1550-1070 BCE), World Archaeology 53/3 (2021), 401-418, https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2021.1999853

Walsh 2022 = Walsh, C., Marginal communities and cooperative strategies in the Kerma pastoral state, JNEH 10 (2022), https://doi.org./10.1515/janeh-2021-0014